On the road with the jamboree called the Rajasthan Kabir Yatra, which took place late February 2012, in and around Bikaner. Vipul Rikhi travels. In this third and final edition, the remembered pleasures of constantly arriving in a journey, expressed in material pleasure and that which strums the soul!

Three whole bus-loads of people are hurtling through the desert, knocking on from village to village. I am one among this loaded population. Each morning we pack our bags and head to another point in the desert, our faithful bus-steeds conveying us. We went thus to Momasar, Sinthal, Napasar, Jamsar, Pugal and Diyatra, crossing Bikaner twice on our way. The yatra is a feast of sights and impressions. Based around Kabir poetry and the folk-musicians who sing it, it yet incorporates many other elements. It is, at one and the same time, a road-trip, a travel into the rural heartland, a journey into song, and a voyage within oneself. Where is this loaded vehicle going? (The body; the bus; the mind; the group?) As we careened through desert villages on a daily basis, this was the question to be considered.

‘Kahan se aaya, kahan jaoge, khabar karo apne tan ki!’ urges one popular Kabir bhajan. (Where have you come from? Where are you going? Consider well your own body, O traveller!)

The Nitty and the Gritty

In a paradoxical conclusion, some of the high points of the journey are what might have been considered its lows. Almost everybody agreed, the hardiness of the travel and the living conditions, mixed with the wine of the music, contributed to the uniqueness of the experience. It was never sure what kind of sleeping conditions (and loos!) we would land up with at night. Often it was ten to twenty bodies piled next to each other in a single room or hall — occasionally two people to a mattress. The nights were cold, and one night in particular was unforgiving. Quilts could run scarce, and people slept with their caps and sweaters or jackets on. Sleep was short. The concerts continued at least up to 2 or 3 in the mornings.

It was also not certain when and where and how the next bath was coming. In Sinthal, for instance, where we were in a school for our afternoon rest, there were plenty of bathrooms available but no buckets or mugs. This is when the famous ‘Pandeyji ki balti’ (the bucket of the venerable Mr Pandey) came to my rescue. One of the schoolboys guided me towards the mysterious Pandeyji, holding court in one of the hostel rooms. Pandeyji had a balti and he was most forthcoming — he oozed bucketfuls of generosity. After washing my hair of the desert sand, I had occasion to recommend the wonderful Pandeyji and his balti to a few other of my co-travellers.

Places and Food!

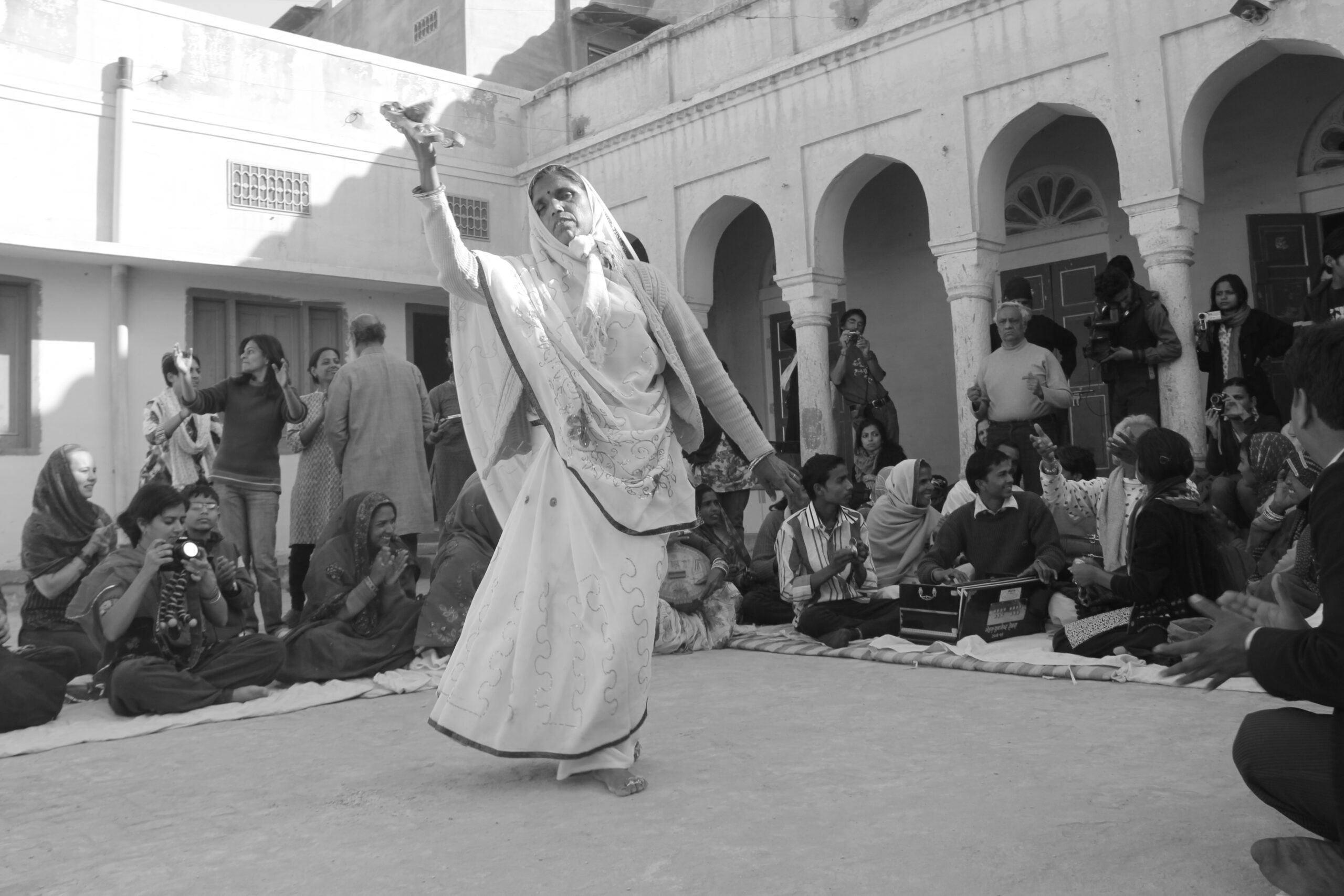

There was this wonderfully mysterious cycle of arriving at a place at night, inhabiting it nocturnally, and then experiencing it anew in broad daylight as we awoke into a fresh, new day. In Napasar we spent the night in an old haveli with an inner courtyard. The cold and the darkness showed us a completely different picture from the warm sun lighting up this space in the morning. Song and dance spontaneously broke out in it.

There were two wonderful temple complexes that we encountered on the way: Baba Gangainath Dham in Jamsar, with the desert landscape stretching out in all four directions around it, and into whose courtyard the setting sun streamed in scarlet, casting dark shadows of the singers and dancers on the glowing red walls; the second was the Dharnidhar Mahadev Mandir on the outskirts of Bikaner, with a great sense of peace and calm, and the steps outside of which turned into a magical amphitheatre-like setting for the evening concert.

It was also here that we were treated to a full-on traditional Rajasthani meal (with ghee being the main ingredient in everything!). The goods were as follows: bajre ki roti (with ghee), sweet churma (also with ghee), bajre ka khichra (more ghee), kadhi, and badi, and phali ki subzi. All that ghee certainly helped with inner lubrication in the extremely dry desert air. At most places, however, meals consisted of the humble puri (easier to make in bulk than chapattis) and aloo ki subzi, both generously dripping with oil.

Another great stop on the way was the dhuni of Jageri, a small shrine in the middle of vast fields of mud quarries and brick kilns. A dhuni is a place for those struck by the sound, singing their own tunes, and it

certainly felt that way as Vedanth broke out into ‘Bhajo re bhaiya Ram Govind Hari’ in an American Blues style on the guitar. This took place on the steps of a picturesque lotus pond, where the water was low and the lotuses yet to bloom, but where the light was golden and the air cool.

Companions and Conversations

Part of the great fun of travelling with over 200 people is that you’re bound to run into at least some that you find interesting. (Stendhal, the French writer, has a great phrase to describe this. He calls them ‘elective affinities’.) I personally couldn’t get over the cuteness of the 14 young Kashmiri girls who dropped in (sponsored by the Borderless World Foundation) for half of the yatra. I chatted with Bilqeesa and Tabish as they gushed about the sand of Rajasthan (no sand where they come from).

Another interesting conversation I had was with Siddharth Panwar from Delhi. Siddharth set out in search for Kabir to look for similarities, for commonalities, with what he called his ‘foundation’, Vedanta. His point was that whatever is true would be the same across Vedanta, Kabir, Sufism and other traditions; the differences would be the fluff, which he could drop. When I asked him what he meant by ‘foundation’, he replied that for him it meant that which remains, what you can absolutely rely on, when everything else around you falls apart.

Bus Banter and Jams

Part of the frolic was the daily travel by the buses through the intense glare of the desert. Lots happened in the buses — and each bus had its own share of fun. One afternoon, on the way to Pugal, Kaluram Bamaniya proceeded to the front of the bus on being requested to sing. ‘Can’t leave the stage, even in a bus!’ quipped Prahlad Tipaniya, his compatriot from Malwa. When Kaluram couldn’t get going with his singing, Prahladji observed: ‘Dor dheeli hai. Khoonti tight karo!’ (The strings of this instrument are loose. Tighten the knob!)

When Kaluram finally did sing, it was a Meera bhajan which said, ‘Aakhi raat ko bajave Kanha bansi re, sove na sova de sari gujariyan ne.’ (Krishna plays his flute all night, not sleeping himself, nor letting the gopis sleep). Prahladji jumped in once more, this time in Krishna’s defence, asking Kaluram why he was defaming a god who encourages everyone to sleep peacefully at nights. More fun was had in most of the bus rides, as the singers and musicians rode with us and jammed with each other, and even the non-singers could not be restrained from singing!

The yatra caravan arrived in the city of Bikaner on the seventh day. The journey concluded. People dispersed to shop for leheriyas and bel ka sherbet, among other things, at the end of what had been a great musical road-trip. The sense of travelling with song, with singers, with oneself and with others lingered in the air like a note heard long ago and still not forgotten.